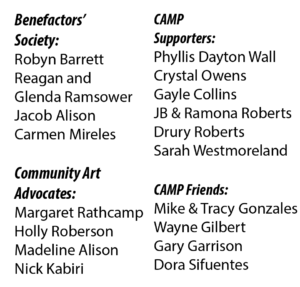

Sponsored in part by a grant from the Sybil B Harrington Endowment for the Arts through the Community Foundation of West Texas

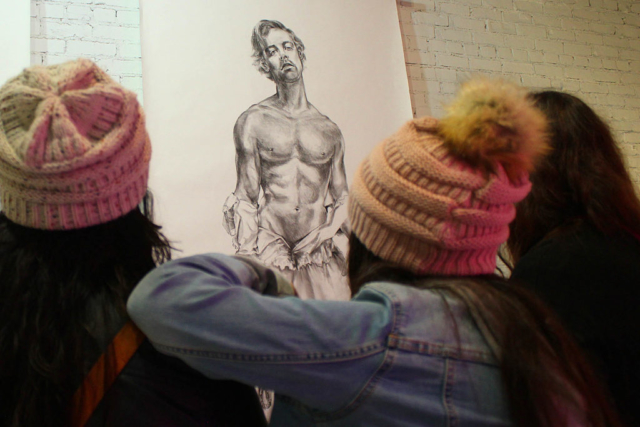

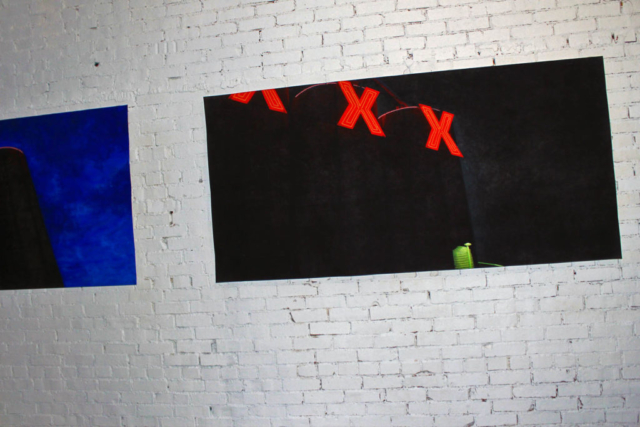

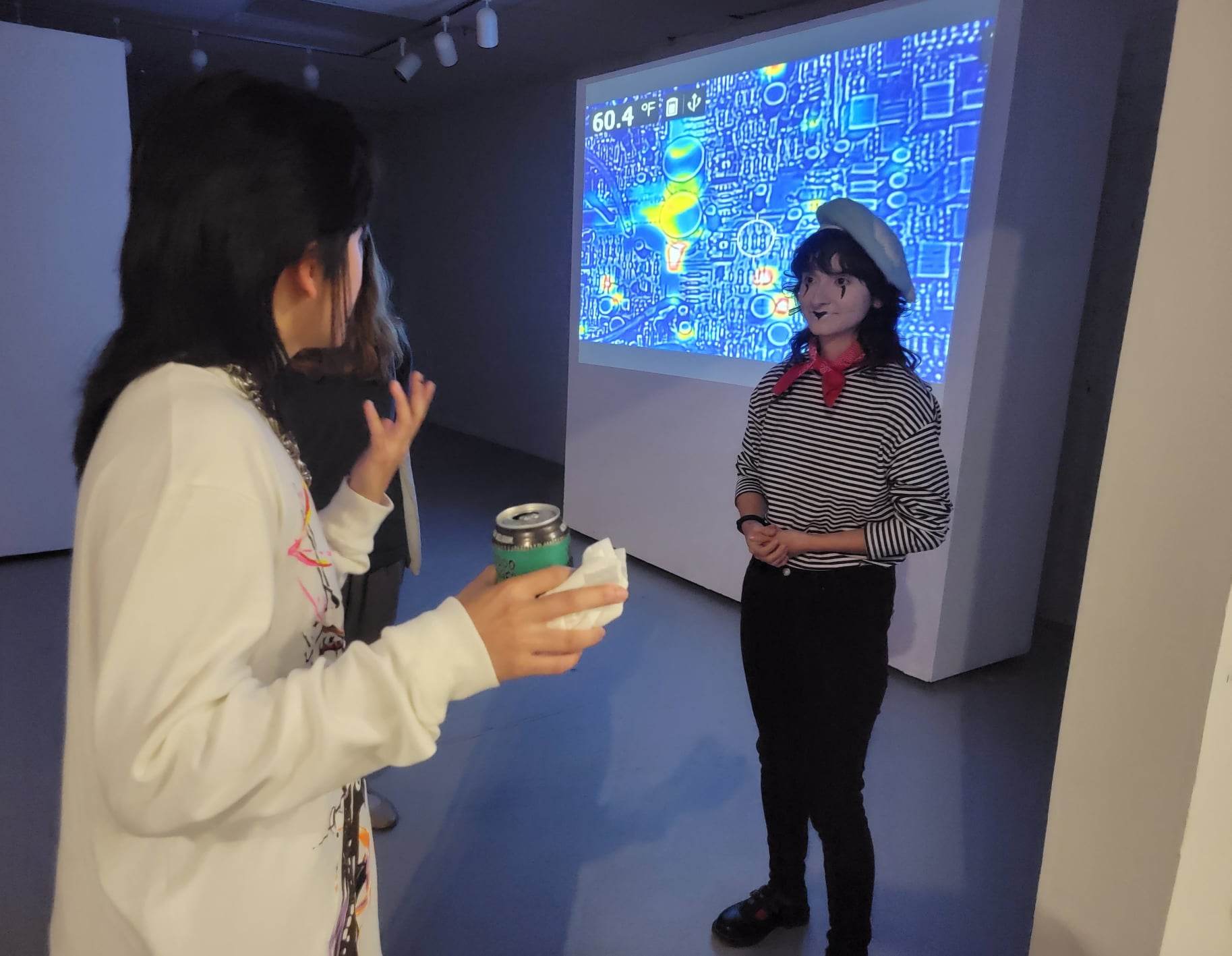

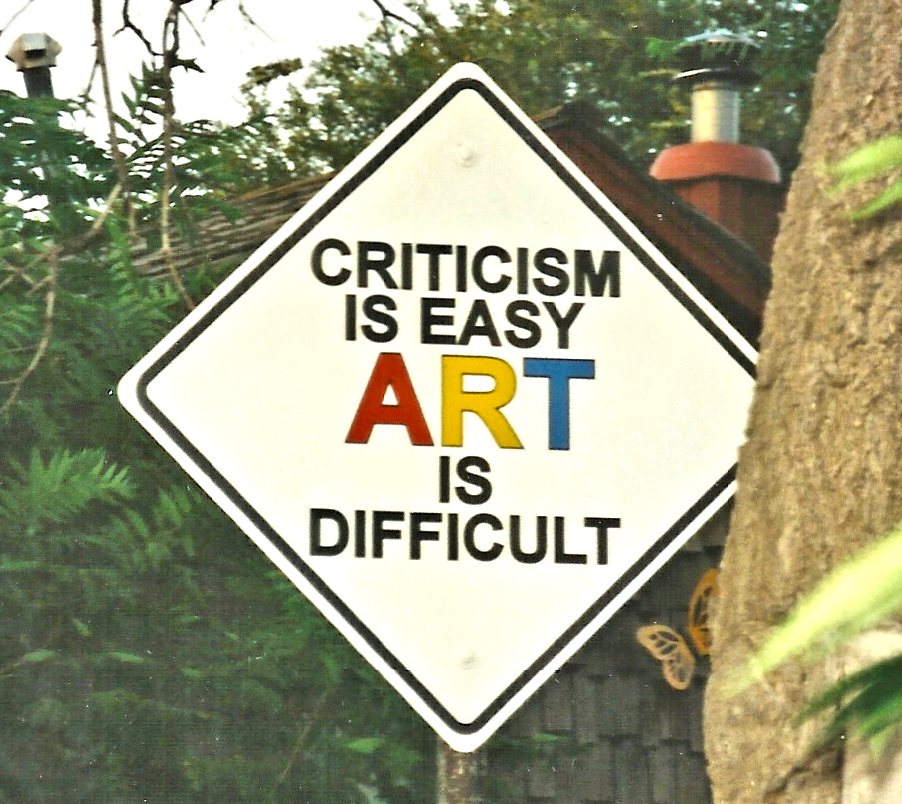

The ART Signs

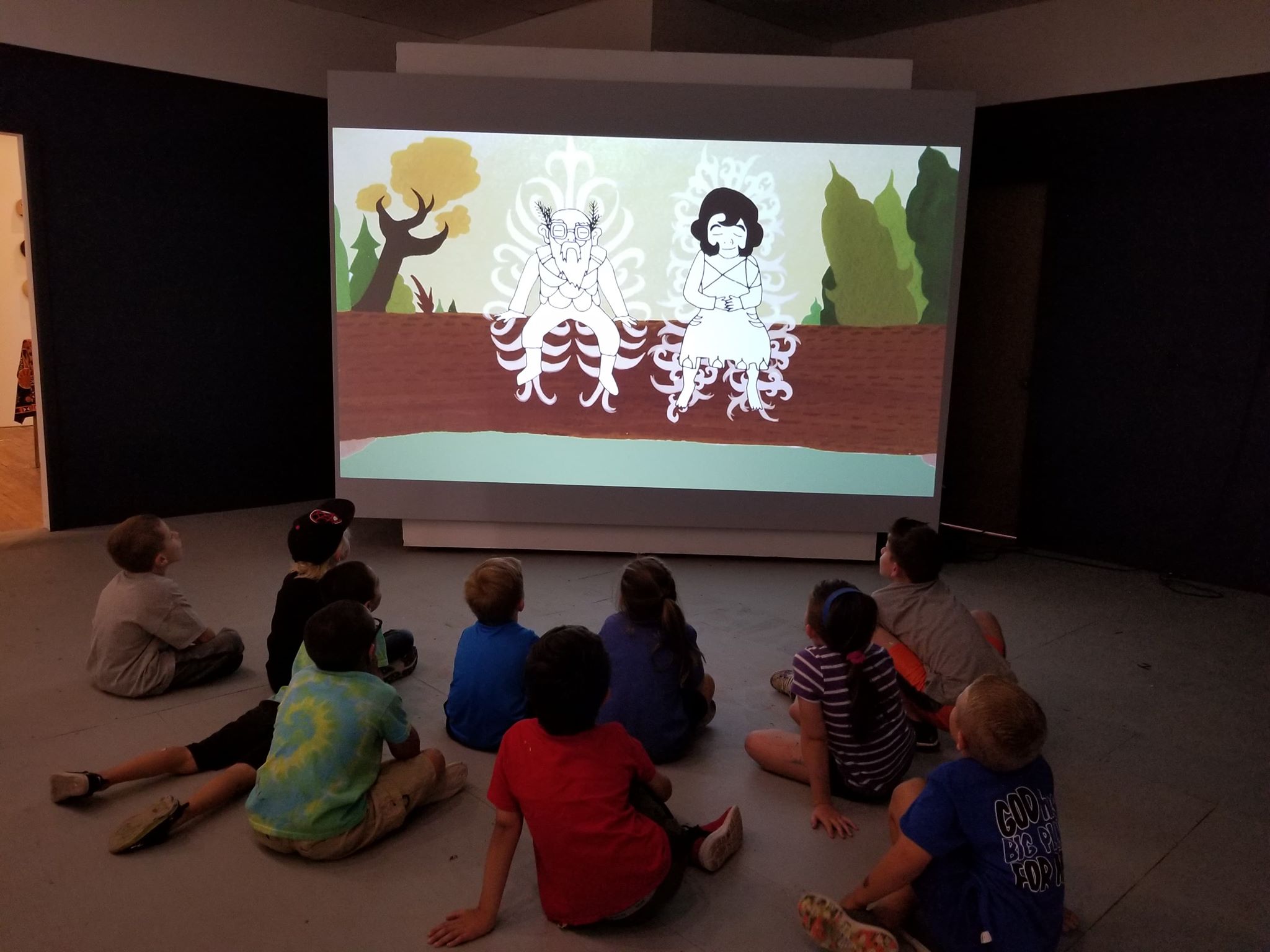

In the mid-nineties, an art collective called the Dynamite Museum put up over 3,000 signs all over Amarillo. These signs took the form of a diamond-shaped street sign, but rather than service related messages of civic signs, they had strange phrases and unusual images. The first signs were put up illegally, put as the p

roject progressed, the sign were installed in the yard of the citizens of Amarillo. The process of getting a sign was as unique as the signs themselves. A 1959 pink Cadillac would prowl neighborhoods and stop at the houses of those people who were in their yards. They would be shown a stack of polaroids of signs. If they selected one, then a week later, a suburban with moose horns and a trailer full of signs followed by a procession of equally strange vehicles would arrive at their house. A swarm of freaks would emerge and install a sign in their yard, spouting numerous theories on the motivations behind the project. While many of the signs have since been removed, there are certain streets around where the sign still inform the public of the need for non-sense.

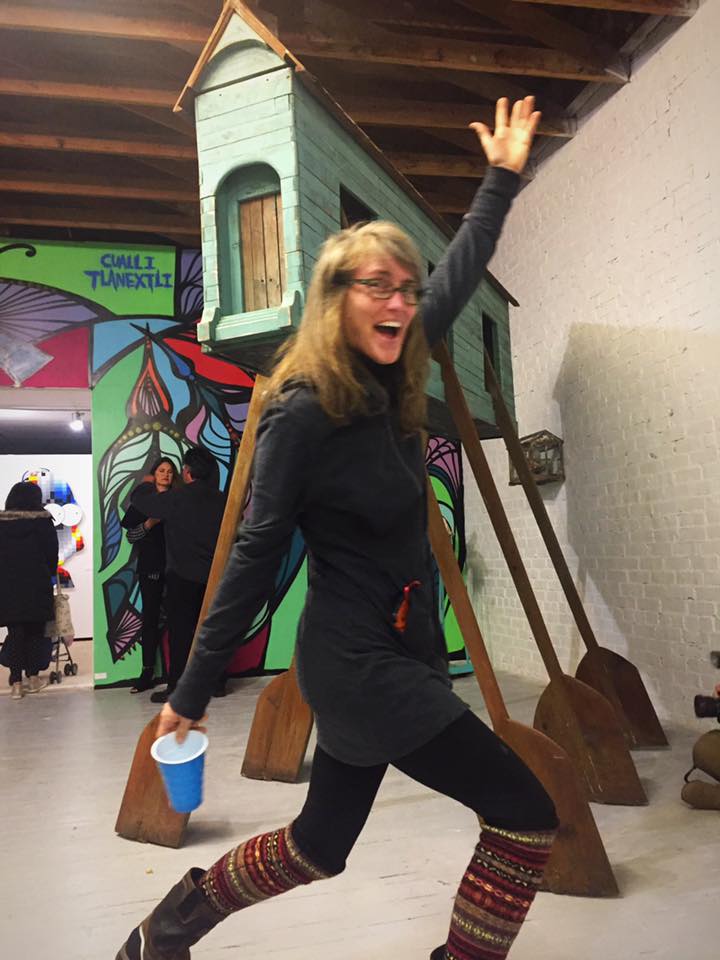

The display of signs in the Yellow City Art Exhibition focuses on the ART Signs. This series of signs proclaimed the importance of art and revealed the true motivation of the Sign Project. While this project definitely change the landscape of Amarillo for a period of time, its impact is much greater on a social level. Many of the artists who participated in the project went on to pursue careers in art, and some of whom are in this exhibition. The signs showed us that art is big enough to encompass an entire city. They were tangible exposure to the role of art within a community. The sign project taught us that artists are vital to culture and validified our purpose to show humans their own true nature.

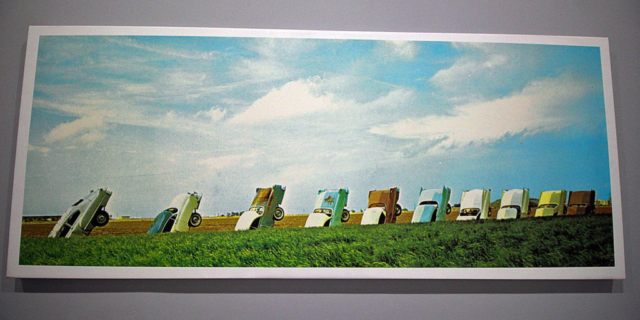

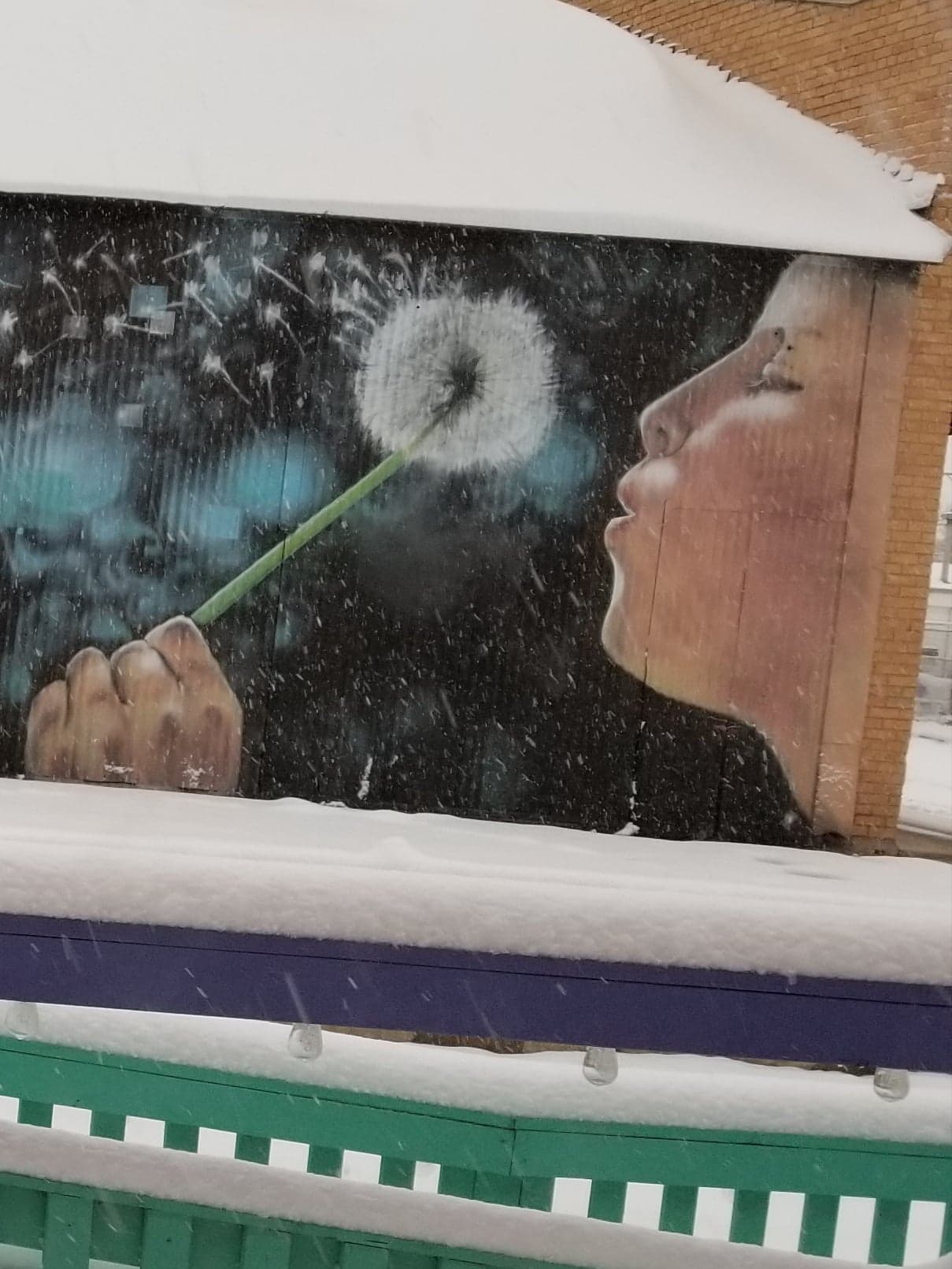

The Cadillac Ranch

In June of 1974, the Ant Farm buried 10 Cadillacs in the ground in a field along Route 66 as a monument to greatness. The Ant Farm where a group of underground architects from California who had found a shared interest with patron Stanly Marsh 3 in roadside attractions. The inspirations for the sculpture are numerous, from lawn darts to dolphin tails, but the most obvious is an advertisement for Cadillacs documenting the rise and fall of the tailfin. Like the ad, the cars are place in order of their manufacture dates, starting with a 1949 Club Sedan and ending with a 1963 Sedan de Ville. On occasion, the rumor that the slope of the cars are based on the slope of the Pyramid

s of Giza, which is a mistruth. Not The Pyramids is a photo comparison of the Ranch, one taken by Wyatt McSpadden taken shortly after construction and the other by Jon Revett, taken in October 2018. This image shows the degradation of the sculpture, which is quite drastic when contrasted the reprint of a postcard showing the Ranch in its original glory. A recent survey estimated over one million people visit the Cadillac Ranch per year. Currently, plans are being made to preserve and sustain the work so it can continue being the American icon that it has become.

Amarillo Ramp

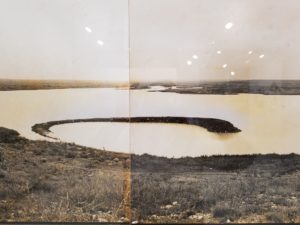

Amarillo Ramp exemplifies the Land Arts movement and completes Robert Smithson’s trilogy of earthworks. The Ramp unified the design elements of his Spiral Jetty in Utah and Broken Circle/Spiral Hill in Holland into sloping 150’ circular ramp that rose out of an man-made lake in the Canadian River breaks northwest of Amarillo. Since its construction, the dam that held the lake has broken and the dry lakebed has become a fixture of the everchanging aesthetic of the work. Influenced by the

rock monoliths in northern Europe and the Native American burial mounts in Ohio, Smithson aspired to build monuments that operate on a geological time scale by using industrial tools to make his mark on the earth. Unfortunately, Smithson died in a plane crash surveying the armature of Amarillo Ramp

before its completion in July of 1973, and it was finished posthumously in the following August by his wife, Nancy Holt, Richard Serra and Tony Shafrazi. Since then, it has become “the most famous, unknown sculpture” in Amarillo, attracting art pilgrims from all over the world, with very few local visitors. This may be partly due to the difficultly of procuring a visit to Amarillo Ramp. It is impossible to find and one must know who to contact for a tour, then the weather has to cooperate because the sculpture is hidden in an active cattle ranch. The challenges of a Ramp visit become part of the experience and amplify the entropic intentions of Robert Smithson. Once visitors consider the effort and time it took to see the earthwork, they will never be the same and can begin understand their place in great expanse of time and space. The two Amarillo Ramp displays reinforce this big picture idea. One is a photo by Wyatt McSpadden that has suffered the effect of time, much like the sculpture itself and the other is a collection of photos, one of which is an restored photo shortly after construction and the other seventy-five were taken from visits over the last eight years.

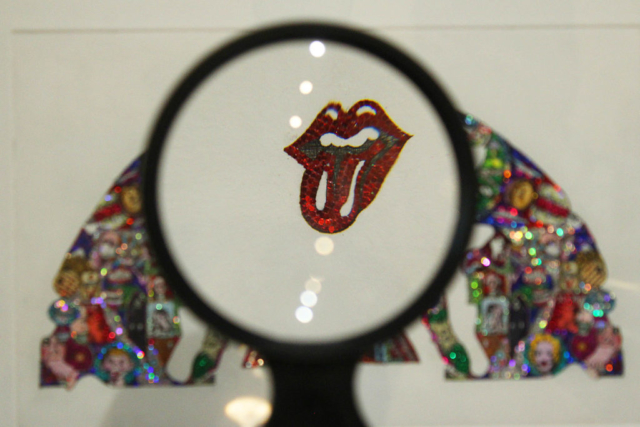

Ed Rucha’s Standard Oil Stations

Ed Rusha is arguably the most successful painter working today. He also also had success with other media, and some of his earliest forays involved the idea of artist books. His first book is called Twentysix Gasoline Stations, which was a collection of photographs he took on several drive done Route 66 between his boyhood home of Oklahoma City and his new home of Los Angeles. The real subject matter of these books is not the obvious. They are not about gas stations. Rather, they are conceptual art projects that show the variation of an idea.

Ed Rusha is arguably the most successful painter working today. He also also had success with other media, and some of his earliest forays involved the idea of artist books. His first book is called Twentysix Gasoline Stations, which was a collection of photographs he took on several drive done Route 66 between his boyhood home of Oklahoma City and his new home of Los Angeles. The real subject matter of these books is not the obvious. They are not about gas stations. Rather, they are conceptual art projects that show the variation of an idea.

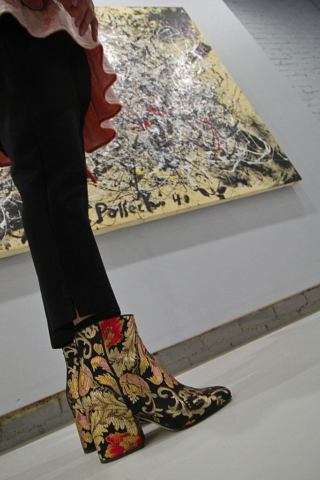

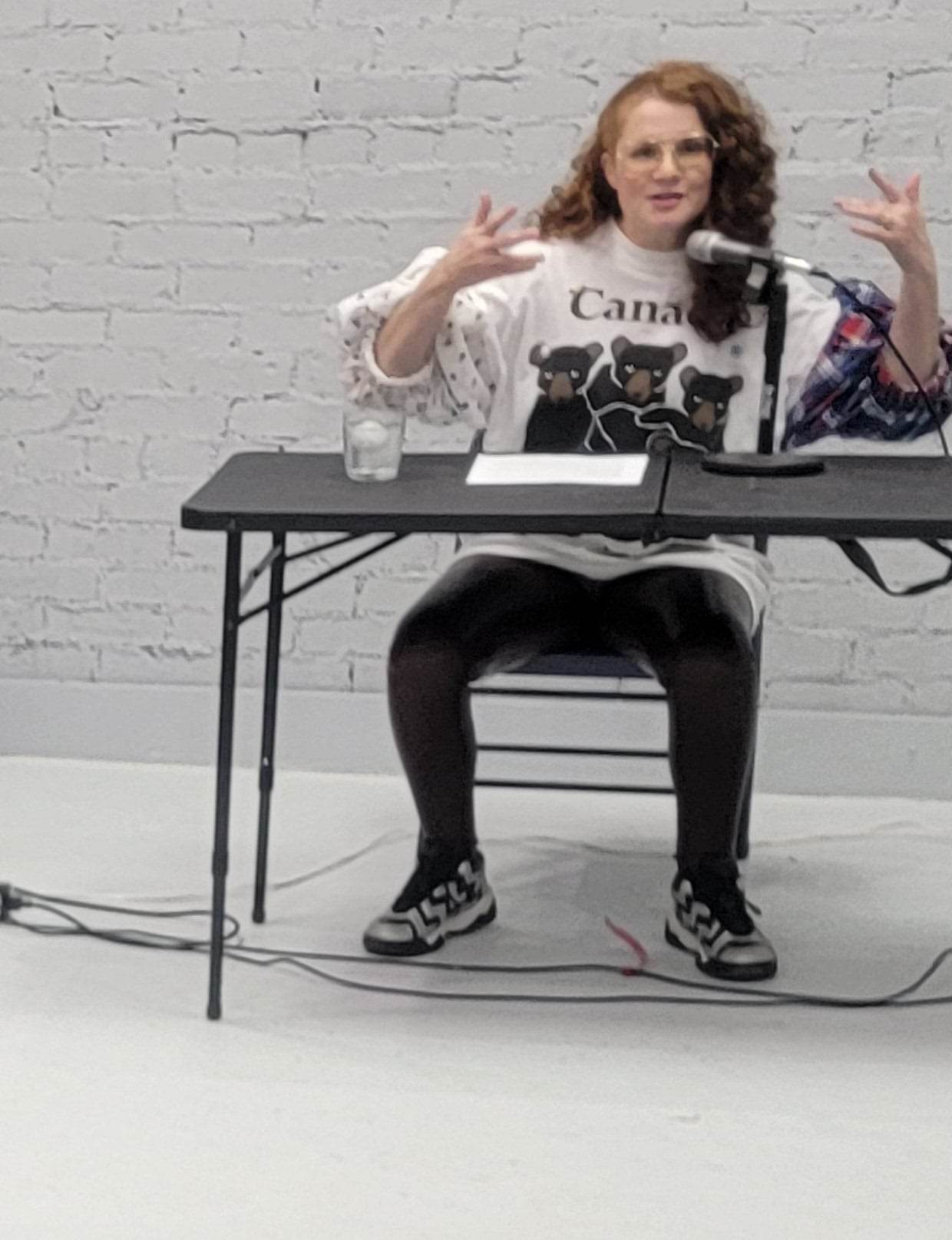

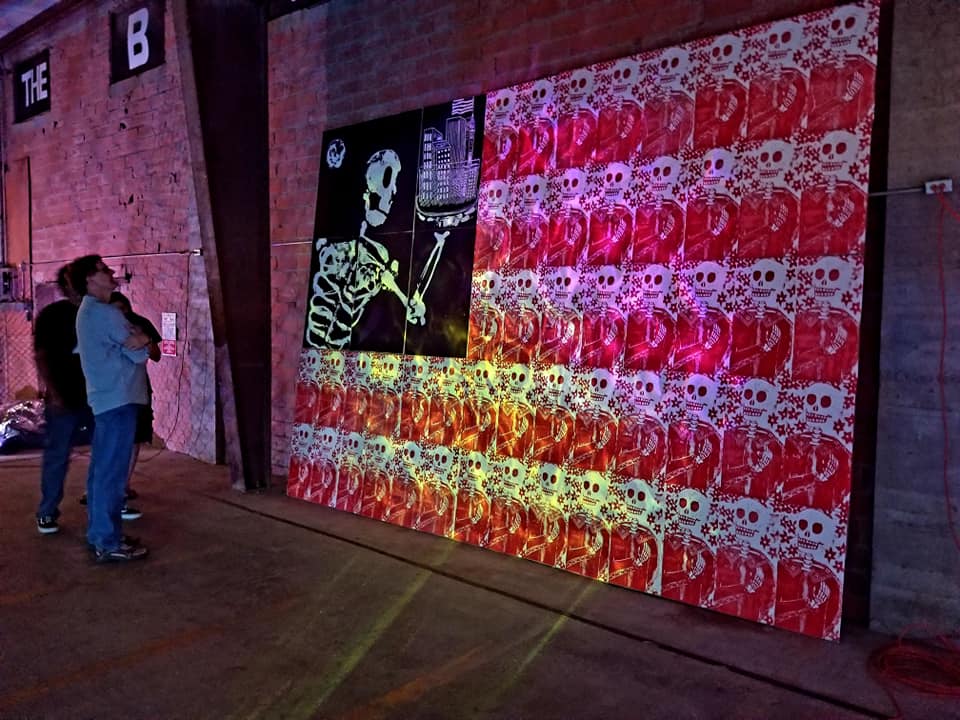

The Glacier Project

The Glacier Project is an interactive installation. Revett was given a palette of old record albums with caveat of not reselling them as music recordings. He decided to transform them into art by screenprinting tessellations on the covers and covering walls with them. He has done multiple installations of the Glacier Project all around the country, and each one exists only for the duration of the exhibition. The public is welcome to purchase records and remove the records during the time it is up, thus facilitating the “melting” of the Glacier. The installation for the Yellow City Art exhibition is inspired by Bruce Nauman’s Performance Corridor, and all proceeds from the record sales go to benefit Contemporary Art Museum Plainview. The suggested price is $20 per record, which Revett will sign and number them to complete their transformation into works of art.